How AVs will make traffic worse

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) are always in the news, and in a way near and dear to me. Growing up in suburbia and loving cars, I had long thought that AVs were the solution to every answer about traffic, parking, land use, etc.

Now that I’ve learned more about planning, design, and math, I believe that the issues are more nuanced. The experiment of suburban sprawl—made possible by cars—was said to be the solution to dark, dirty cities. Seventy years later, we are seeing a return to those same cities. Overly positive discussions about the future of AVs sound like the 1950s sprawl rhetoric, which is worrying. AVs will arrive, like it or not, but the discussion can be re-centered around realistic pros and cons.

I recently had an interesting discussion with a thought leader about the future of AVs. While we didn’t come close to finishing our debate, I wanted to elaborate on some of my arguments that lead to a larger theme, which turns much of the AV logic on its head:

Autonomous vehicles will not improve traffic, but rather make it worse

Background

As more AVs enter the transportation system, will total miles go up, or stay the same? The thought leader I spoke with believes that because stats show most vehicle trips are used for errands (42%), the ratio of trips carrying passengers (85%) vs carrying cargo (15%) will change, while total miles will stay the same. So there will be more carrying cargo trips. (Other AV thought leaders believe the total number of miles will increase.)

Even if the current level of total miles driven stays the same, but the ratio changes, I do not believe that traffic will improve as a result of AV efficiency. Below are several reasons why:

- Any efficiency gains made by AVs will be offset by the greater average vehicle size on the road

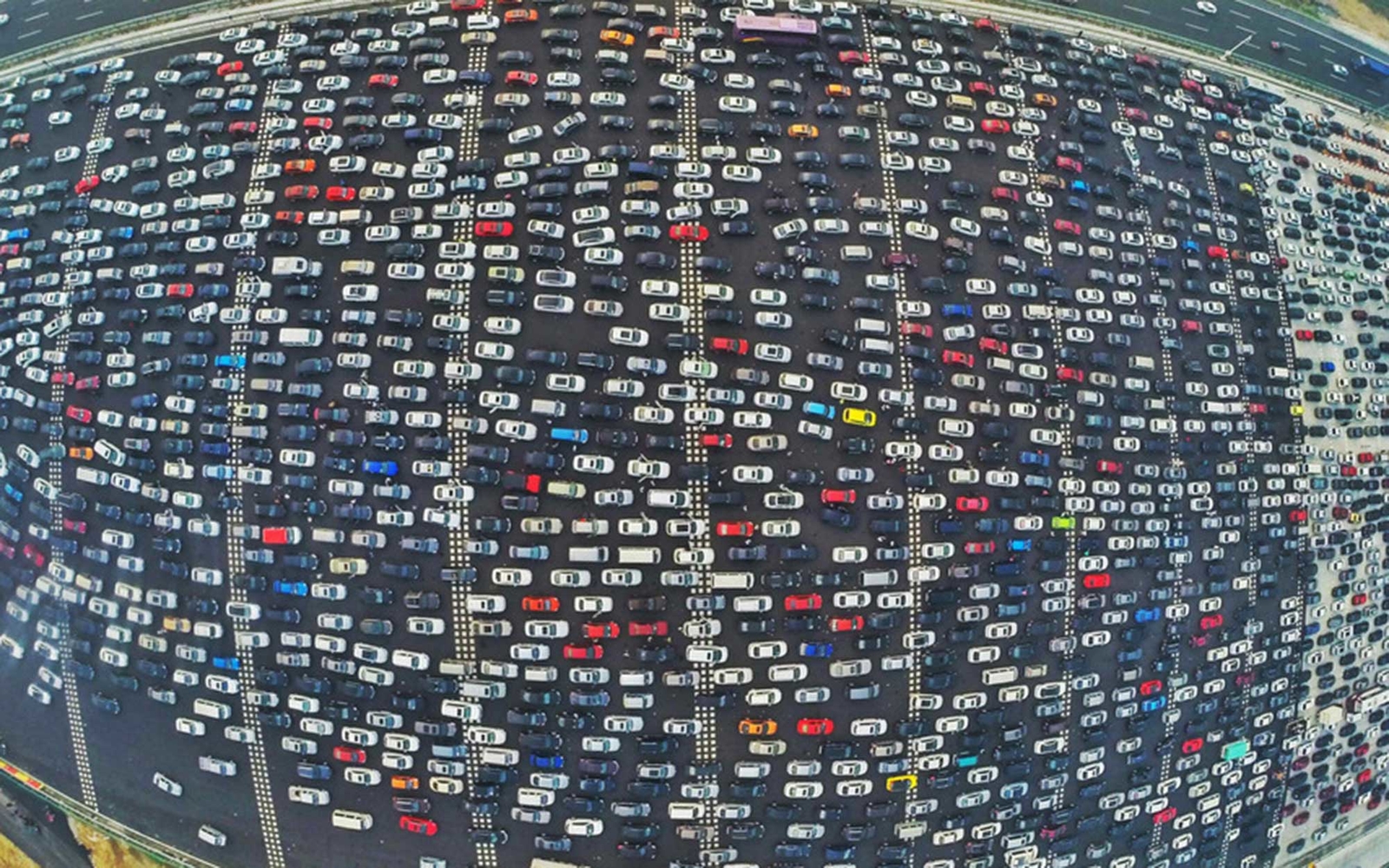

Even if the ratio changes, and there are more carrying cargo trips—i.e. more delivery trucks, 18 wheelers, etc.—traffic will still be an issue, because cars are fundamentally spatially inefficient. This problem is not social, economic, or moral, but rather geometric.

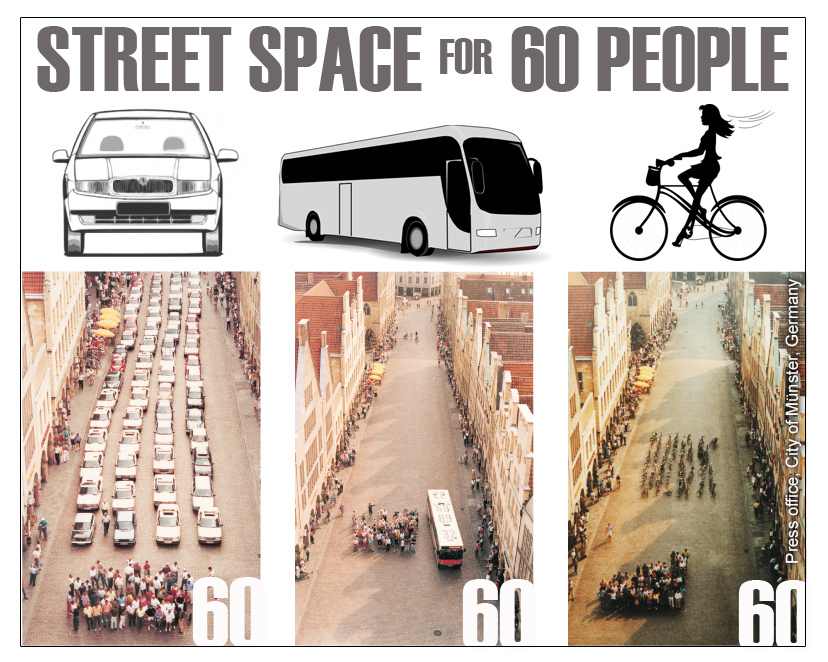

In the image comparing the amount of space a bus takes to carry 60 passengers, versus the number of cars, it’s easy to see the bus is more efficient. (Of course, there are issues with this analysis, but considering how often tech start-ups re-invent the bus, I’m fine with using it.) As the average size of vehicles on the road increases (cargo delivery vehicles tend to be larger than passenger vehicles), they will of course take up more space.

If you’re not convinced, then take a look at the analysis of how more online shopping has already been blamed for significant traffic increases across the US. As more people shop online and more gets delivered, won’t this process get worse? What if delivery trucks become smaller, as last-mile delivery gets solved and it gets easier to deliver things? Then there are going to be more, smaller trucks on the road. See the image comparing the car and the bus for what will happen.

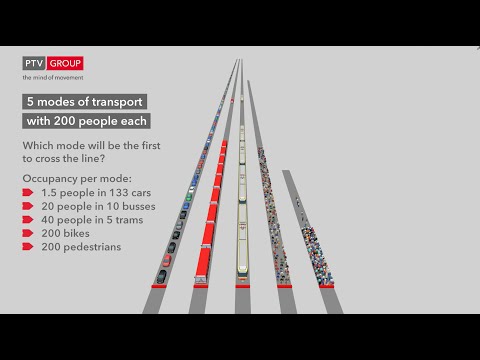

What if total average vehicle size decreases? AV proponents often state there will be a wider variety of cars, some quite small, to make the transportation system more flexible. There likely is a crossover point where smaller total average vehicle size will balance an increase of smaller vehicles. But if you think making vehicles smaller and smaller makes sense, then you should see the video below comparing number of current-size cars in the same space as pedestrians, the most efficiently sized unit of transportation. (I’m being somewhat facetious, and urban planning is a somewhat separate issue, but it’s still relevant.)

- As car utilization rate goes up, the whole transportation system will become more inefficient.

Because car utilization rate by owners is between 2-5%, most cars go unused much of the time. And since most trips are for errands, there will be little need to own a car, so vehicles will be used more and rented out more. The standard argument is that a higher utilization rate will make the whole transportation system more efficient and lower traffic.

However, as the average utilization of a vehicle goes up, this means it is on the road more. So any increase in vehicle utilization rate has to correspond with a total decrease in total vehicles on the road—otherwise there will be more traffic. Look at what Uber and Lyft said about how ride share would lower traffic, but by their own numbers ride share has significantly increased traffic.

However, as the average utilization of a vehicle goes up, this means it is on the road more. So any increase in vehicle utilization rate has to correspond with a total decrease in total vehicles on the road—otherwise there will be more traffic. Look at what Uber and Lyft said about how ride share would lower traffic, but by their own numbers ride share has significantly increased traffic.

Also, one of the joys of driving is the immediacy—hop in and start going immediately where you want. If you no longer own a car, you have to wait. How much time will you wait to do an errand, or go to your friend’s house? Will people be willing to wait more time than for a bus? In the city, wait times would likely be low. In the suburbs, where a system like this is in some ways more needed, wait time could be considerably longer. Will AV transportation companies allow users to pay more to jump the line, to get their car faster? Why wouldn’t they?

The greater point is that regardless of how efficient car utilization becomes, or package delivery, etc., none of these makes the whole system more efficient, which is the ultimate metric for measuring traffic.

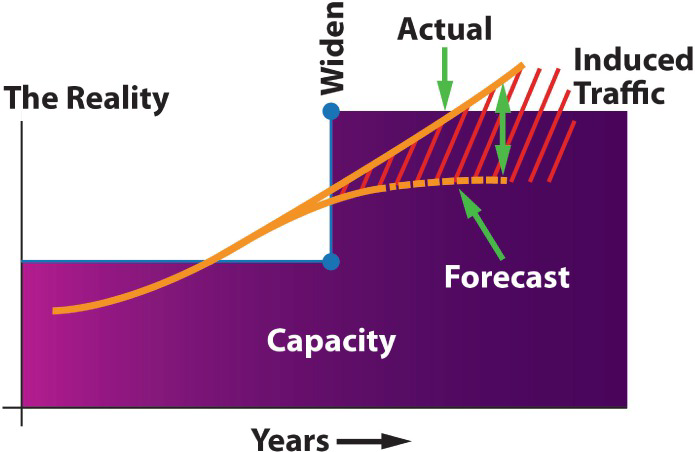

- Ultimately, traffic is an induced demand phenomenon.

This means that as more capacity is created, demand will be created to use that space. (This phenomenon has been reported around the world for decades.) Both lane widening and new lane construction apply to this. Making car transportation more accessible and efficient is effectively “adding capacity” to the road system. So AVs will cause more demand, and create more traffic. Again, see the links about Uber and Lyft creating traffic.

As it is, our country is having trouble paying for maintenance of all current roads, let alone build new roads. If cars are used more, and more efficiently, then roads will be used more. In a future where AVs allow greater vehicle usage and optimized paths, roads will get even more worn. How will we pay for this?

Conclusion

There is a lot of data to look at about AVs, and a lot of ways to interpret this data. For those who can predict the direction of this new transportation system, there is a huge market and a huge profit waiting. So, what do you think? Will AVs improve traffic, or make it worse?

Did my analysis miss something? If so, please let me know in the comments! I’m always looking to improve and get feedback.

Is there an aspect of AVs you’d like me to write about? I plan to continue this series, but would be happy to focus on a particular area.